There she goes, again

On formative media, the search for perfection, and "The Parent Trap" (1998)

Last year, when I decided to cut my hair short for the first time in over a decade, I brought a photo to the salon for reference, as one does. When I came out, freshly chopped, my sister was one of the first people I sent a selfie to. She’s always been a top-tier hype woman, enthusiastic and honest when needed.

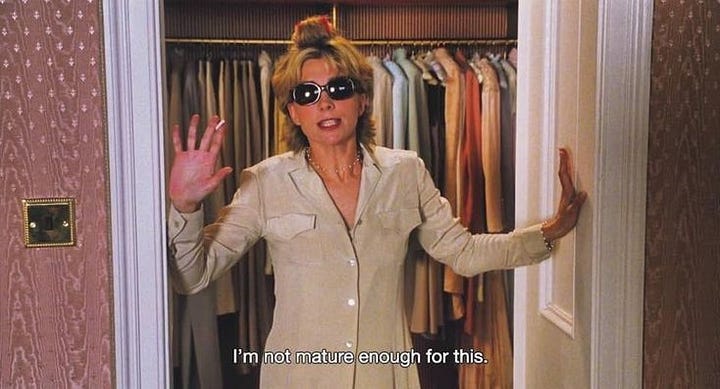

TO DIE FOR, I’m literally obsessed, she texted back accordingly in short order. I sent her the reference photo I had shown my hairdresser, shown to the left below—which was actually not a photo, but a film still. It features Natasha Richardson, in the role of very cool, very anxious mom Elizabeth James, in the 1998 film The Parent Trap.

While I’m a person with arguably too many moodboards, obsessively organized into subsets of mood, this was far from being a purely aesthetic choice.

My sister and I grew up in a movies-only household—no cable, no TV except PBS Kids. In the armoire that served as half pantry, half repository for my father’s film collection, we filled a shelf with thick, white-plastic Disney VHS tapes. The one we pulled out most by far was The Parent Trap.

A quick synopsis for the uninitiated: the titular parents fall madly in love, and get hitched, on an ocean liner. They have twins, then shortly after get divorced, each taking custody of a daughter. They never speak again or tell either daughter of the other’s existence—until, by a twist of fate, the two meet at summer camp. When Annie and Hallie (both played by Lindsay Lohan) discover they’re not just freakish lookalikes, they make a plan: to switch places and convince their parents to get back together.

Hallie flies to London to meet her bridal designer mother Elizabeth (Richardson) for the first time, and Annie heads to Napa, California, where her dad Nick (Dennis Quaid) owns a vineyard. When a gold-digging young potential stepmother enters the picture, the girls rush to reunite their parents, and hijinks ensue.

Yes, parts of this premise are wild. Hold your questions, please. I’ll get there.

I’ll never quite know why my sister and I latched onto this film the way we did. Maybe it was premonition, intuiting our own parents’ divorce a few years later. Maybe we found it easy to slot into the twins’ neat opposites: prim, pearl-wearing Annie and spunky, glitter-nailed Hallie. But it wasn’t just about watching the film. We learned the secret handshake Annie teaches Hallie (so the latter can impersonate her). When we were allowed junk food, we often picked Oreos (though not with peanut butter, like the twins). We replicated, endlessly, the scene when the two play poker—we fought over who’d wear sunglasses and pronounce Hallie’s opening line (“I’ll take a whack at it”), losing and then winning back trinkets, nail polish, and petty change from each other. We drew a thread between the twins’ camping trip in the film and our own yearly trips into the mountains of New England.

Like every young girl eventually does, we’d found an obsession.

I can’t speak for my sister, but I can pinpoint the peak of the Parent Trap fixation: our own parents’ real-life divorce.

They finalized the paperwork the year I turned eleven, the same age as Hallie and Annie. At that point, I was not adjusting well—to our parents dating new people, to moving between two households, or to being the only one of my friends with divorced parents. My parents’ explanation—we tried really hard, it just wasn’t working anymore—felt totally inadequate to an eleven-year-old, especially because they remained friendly. Maybe, I reasoned, they just needed a break from each other. Maybe I just had to make them spend more time together—or, if I was really following the film’s blueprint, lure them onto a boat over a candlelit dinner—and they’d remember why they fell in love in the first place.

Thankfully for me and for my parents, I never acted on it. When my father introduced the woman who’d eventually become our stepmother, she was much too nice for me to even consider any of the hijinks that the twins pull on Meredith Blake, the 26-year-old marketing bombshell who’s trying to marry their millionaire father. At some point, I became faintly embarrassed that I’d ever thought a parent trap was plausible. Grown-ups know when to move on.

My sister and I were each other’s only constants in a haze of new spaces and routines. This should have made us anchors to each other; instead, we turned on each other, fighting nonstop. We knew exactly which buttons to push. And as we grew into our teens, we branched away from each other, into our own interests: I auditioned for musicals, she tried out a half-dozen sports, I wrote songs, she sketched fashion designs. The things that had once bound us together—including the film we’d loved so much—receded into the background.

After moving to New York for college, and then staying for my first shiny post-grad job, I started seeking out nostalgic comforts. Books I loved as a kid, music my father used to play in the car, French films as substitute for my mother’s voice. Call it early-adult growing pains, reaching for the familiar when the life you’re making for yourself is everything but.

Some things we love get better with time—lyrics that gain new meaning, a trinket from a trip we remember fondly. Others start to lose their shine, or turn thin and transparent—a piece of clothing that doesn’t fit or reflect us anymore, a friendship based on habit rather than intimacy.

In this rediscovery phase, I stumbled back onto Parent Trap. I blithely expected it would fall squarely in the first category.

Oh, boy.

On that rewatch, questions I’d never considered popped up at an alarming rate:

What judge on earth would’ve approved a custody arrangement in which each parent raises one sibling and they never introduce them to each other?

How did the twins end up at the same New England summer camp, a place without any explained significance to their parents? You want me to believe those odds? (Also, those cabin names did not age well.)

Speaking of sending their daughters a six-hour flight away, how did I not catch earlier that these parents are rich? Elizabeth lives in a tony London home and mostly leaves her boutique to underlings; Nick, despite Dennis Quaid’s deceptively rugged everything, owns an endless vineyard and a house that dwarfs any place I’ve lived, ever. Both have household help: Annie’s acerbic butler, Martin, and Hallie’s lovingly-no-nonsense housekeeper, Chessy. Wealth does not preclude every problem, but it does create a remove, a lack of relatability. (Partly the Nancy Meyers effect: her characters lean upper-middle-class-and-above.)

The romance plot between Chessy and Martin felt strange to me even as a kid, and as an adult I wondered: why force it, when both characters are so queer-coded—seemingly deliberately? (In a very late-90s, reductive kind of way, but still.) To my previous bullet, it also felt classist: look, the help can fall in love, too. Preferably with each other, though.

I came away disappointed in a way that was, if not familiar, at least recognizable—that storied sense of Growing Up, everything seeming better in your imagination than up close. It was an early, mild taste of the disillusionment that’s now commonplace, when you find out a favorite artist or celebrity isn’t such a great person outside of their art. (“Separate the art from the artist” is not for me, don’t suggest it here, thanks.) Things weren’t so bad that I’d never watch Parent Trap again, but its shine had definitely tarnished.

A couple of summers later, my sister and her boyfriend at the time drove me south to catch a train back to New York after our yearly mountain trip. She’d mostly skipped this trip in her college years to catch up with her hometown friends, so this was the first solid time in a while we’d spent together outside of holidays.

Midway through the drive, she queued up a song and grinned at me in the rearview. You’ll like this, she said. A few seconds later, the unmistakable opening riff to The La’s “There She Goes” came over the speakers. I yelped, and my sister started laughing in delight.

Oh, is this from that movie? said her boyfriend, in the passenger seat. I was astonished. In Parent Trap, the song underpins Hallie’s first taxi ride through London, a montage of shaky car-mounted shots of tourist spots—but how did he know that?

I made a playlist for the whole soundtrack, said my sister, answering me instead of him, still grinning. I listen to it on errands, or on bad days.

The boyfriend twisted around to face me. She had me watch it with her once. You guys watched it growing up, right?

Excuuuse you, it was like, a key part of our childhood, my sister corrected, offended. It’s a sister thing.

Her voice was matter-of-fact over the song blaring from the speakers. Something in me loosened, warmed. Yeah, I said, my voice only a little strangled, a sister thing.

In the last few years, I’ve found the Parent Trap universe seeping back into my own. It had a moment on TikTok, right around the rise of the “coastal grandmother” aesthetic, which draws partly from Nancy Meyers films. I found myself quoting it randomly, dialogue bubbling up from my subconscious like the poems I had to memorize in high school. And when my sister moved a thousand miles south—taking my title of Furthest Daughter Away for the first time—a Parent Trap reference would pop up in our texts every few months.

I hadn’t forgotten any of the issues I’d found with the film. The difference, I think, was getting outside my own head; remembering why I liked it in the first place. Some of my friends also loved Parent Trap growing up, and as we’ve dug into its good and bad facets—Elizabeth’s wardrobe, the evil-stepmom trope, Chessy’s queer overtones, the damn custody thing—it turns out, I can enjoy both sides of the discussion.

About a year ago, I was shopping secondhand and found a gorgeous vintage black cocktail dress. I immediately texted a Parent Trap-loving friend, Is this not THE Elizabeth James dress? She replied almost immediately, Omg. GET IT. (I did. Obviously.)

It’s too dramatic to call this process redemption. It has been, maybe, a mellowing—finding the happy medium between the kind of obsession that can’t stand criticism (stan culture, I’m looking at you) and the kind of moralistic analysis that leaves no room for human joy or error.

Here are some glaringly obvious truths: Any piece of media has flaws. Suspension of disbelief is necessary to many of the fictional stories we absorb. (Note: fictional. I am not talking about current events, though I wouldn’t fault the assumption.) We get older, we change, and we won’t always relate to the things we love in the same way across all of time.

Knowing that, what makes us clip a film, or a song, or a book to our ribs and keep it there like a talisman—despite its failings? What keeps us coming back?

For all its faults, Parent Trap still makes me feel things. That poker scene—Annie’s ice-cold Take a seat, Parker, Hallie pouring out quarters while George Thorogood growls “Bad to the Bone”—is all preteen bravado, a delight to watch. And I’m not a crier, but I cry every time I see the scene where Hallie reveals her real identity to her mother, saying—with all the desperation of an eleven-year-old—I hope you're not mad, because I love you so much, and I just hope that one day you can love me as me, and not as Annie.

I cry hardest when a verklempt Elizabeth wraps Hallie in her arms and murmurs, Oh, darling. I’ve loved you your whole life.

Off-screen, Parent Trap connects me to my younger self: a me that wasn’t afraid to feel things loudly, that made time for dreaming and playfulness—things I sorely need reminders of as an adult. And it’s a tether to my little sister, the Hallie to my Annie (we’re at the end now, so I can admit it: she’s always been the cooler sister). As adults who live a half a continent apart, the film is a mnemonic for our hard-built loyalty, a reminder that as wildly different as we’ve grown to be, we’re still ready to do basically whatever for each other. (Except a switcheroo. Since I’m fair-haired and blue-eyed where she’s a dark-eyed brunette, that one could only work over the phone.)

I hated philosophy in school, not least because the concept of a Platonic ideal sounded, frankly, goddamn boring. I can love the things that shaped me, and the people who anchor me, without demanding perfection from them.

And if you’re wondering why I shared this odyssey with you today in particular (though I’d be surprised, if you’ve made it this far)…

Parting notes—

For its 25th anniversary, Michael Elias wrote a cool piece on how The Parent Trap became a queer classic for Xtra.

If you’re into style, Coveteur has a fun roundup of the film’s best fashion moments.

Did you also grow up with Annie and Hallie? Did you soldier blind through this whole piece and somehow not get scared off? Tell me your favorite Parent Trap references, or which pieces of media were equally as formative for you!

There’s obviously a bigger conversation I’ve only just touched on in this piece, about once-beloved media that involves problematic elements or people. As an ex-fan of several of these, I’ve dug into this massive discussion online at different points, and it’s obviously graver when the issues are of a systemic or marginalizing nature. Quite honestly, nothing I’ve read on the subject felt helpful enough to share with you. Ultimately, only you can do your research and decide your boundaries, what you’re willing to give your time and money to. I’d just hope that we all, myself included, strive to avoid harming others with our choices.

“Verklempt” what a great word 👌🏻 not so common in Australia.